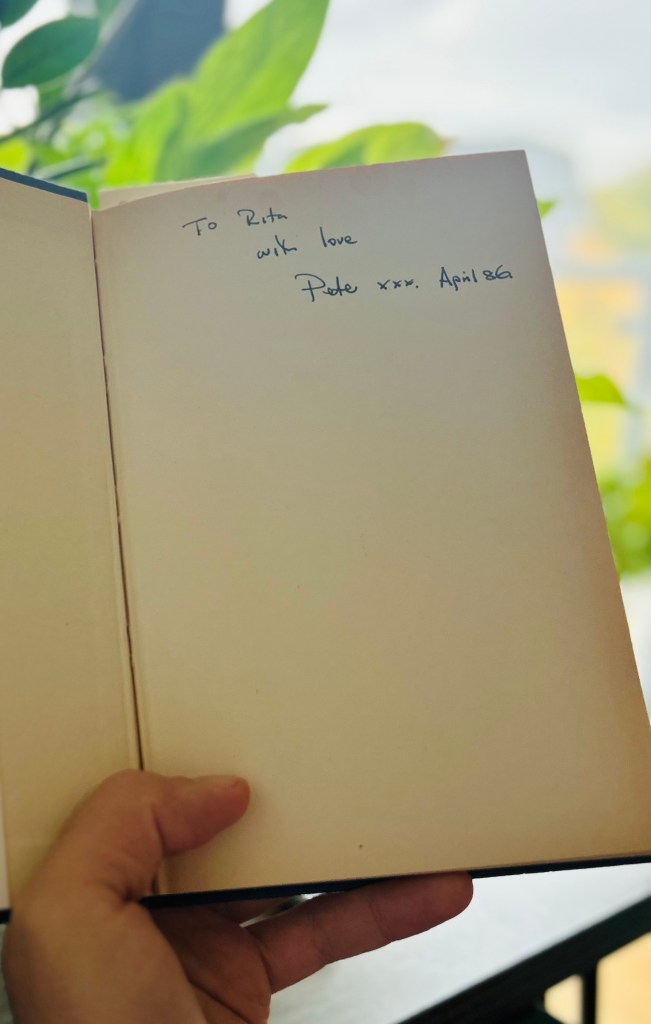

As I usually do, I bought a used copy of this month’s selection for my neighbourhood book club: Hotel du Lac, Anita Brookner’s marvellous 1984 Booker Prize-winning novel about making sense of people and the shame we inhabit. The copy I received was a marvellous 1980s edition, its cover gently worn, the paper slightly yellowed with age. Inside was an inscription in assertive biro: ‘To Rita with love, Pete xxx. April 86.‘

I love finding ephemera like that in used books (once, I found a four-leaf clover that a child had pressed between pages and forgotten in 1972). That simple handwritten note in Hotel du Lac became a fragment of someone else’s life, a small piece of history folded into my own. It reminded me that buying a book is rarely just about acquiring a text — it is, at its best and fullest expression, a gesture of self-formation. Choosing a book can be a conscious act of orienting yourself toward a new way of thinking, a new rhythm of attention, a new life project. In that way, book buying is a practice of becoming.

Every book purchase marks a threshold, a crossing into a new state of thought, feeling, or attention. When I choose a book, I am often choosing not only the ideas it contains but also the possibility of becoming someone who holds those ideas. That threshold might be a commitment to learn something new, to deepen a habit, or to allow oneself to enter an unfamiliar world.

For me, Hotel du Lac became not just a novel but a threshold to conversation — in our book club meeting tonight we will speak about solitude, desire, love, and the quiet transformations of everyday life, I’m sure. The purchase itself became the first step into that dialogue.

Choosing which books to buy is also an ethical act — a choice about the economy of your attention and the kind of knowledge you wish to cultivate. In our age of algorithm-driven recommendations and one-click convenience, the act of selecting a book has become even more deliberate. It is an assertion: of attention, of values, of resistance to the noise of the digital marketplace.

I try to keep this in mind. When I choose a book, I am choosing the kind of life I wish to live. That is why I prefer second-hand bookshops, curated lists, and the serendipity of browsing. The gift of finding a well-loved copy of Hotel du Lac was not just about economy but about entering into a relationship with the book that carries the traces of other readers and a past moment in time.

My first job as a teenager was as a bookseller at Borders Books, and I’ll never forget the linger last hour before closing when the shop was almost empty and I wandered to and fro reshelving books that had been cast aside and getting lost myself in the shelves. There is something profound in the act of browsing: the way attention moves differently among stacks of books, the accidental discoveries, the impulse that turns browsing into a purchase. This ritual carries a rhythm: the searching, the selection, the return home, the opening of the book for the first time. It is a small act of pilgrimage.

This ritual has shifted for me over recent years. I buy more online and second-hand now, but I also savour the moments when I am in a physical shop, taking time to feel the books, the paper, the weight of them in my hands. Buying a book in that way is an act of attention — a slow, deliberate counterpoint to the speed of modern life.

The books we choose to live with often become companions in our ongoing process of becoming. That inscription in Hotel du Lac reminded me of this. A book is not simply an object; it is a living presence. It carries the imprint of its past readers and acquires a new life each time it meets another. In choosing it, we invite it into our own narrative.

Some books grow with us. They take on new meaning as we return to them at different stages of life. They become landmarks in our own inner journeys. It’s for that reason that buying books can be a form of investment in the future self we aspire to become.

When I buy a book, I am buying a possibility: a possibility of becoming a reader who thinks differently, who sees differently, who lives differently. Each purchase is a small apprenticeship in self-making.

Here are some ways to make book buying a mindful practice:

- Keep a wishlist and revisit it periodically.

- Choose one book that challenges your usual thinking every month.

- Seek out books outside your comfort zone.

- Return to books that have shaped you before.

If we approach book buying as a practice of becoming, every purchase becomes a small act of self-cultivation. This month, my purchase of Hotel du Lac was not just for a book club — it became a quiet practice of curiosity, of connecting with a history, of choosing to open myself to a particular conversation. In this way, every book bought with attention becomes a threshold, an ethical choice, a ritual, a companion, and an investment in becoming.

If you choose to see book buying this way, your library becomes not simply a collection of texts but a landscape of your own growth. What will your next purchase become for you?

Upcoming Events

If this resonates, you might enjoy joining one of my upcoming gatherings:

- Mindfulness for Creatives: Cultivating Focus, Flow, and Inspiration: Online, 23 October, 7.30-9.00pm (UK time)

- Stopping the Drama Cycle: A Workshop on Love & Our Limiting Patterns: Online, 3 November, 7.00-8.30pm (UK time)

- Practical Miracles: Practicing the Course Beyond the Book: Online, 8 November, 2pm-5pm (UK time)