Beauty has become strangely suspect in our society today as too indulgent, too easily confused with luxury, escapism, or branding, or too uncaring in a world filled with sadness and despair. We talk about beauty as if it were optional, as if it were something to be enjoyed after the serious work is done. But I’m increasingly convinced that beauty is not a reward at the end of the process. It is one of the conditions that makes a life—or a creative practice—habitable in the first place.

This isn’t a new argument. Elaine Scarry, in On Beauty and Being Just, writes that beauty presses us toward attentiveness, generosity, and care. The great philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch described moral life as a training of attention, where learning to see clearly—lovingly, even—was inseparable from ethical development. Beauty, in this lineage, is not decoration. It is an education of perception.

What is new, perhaps, is how thoroughly beauty has been crowded out of everyday life by urgency, performance, and abstraction. We live inside systems that prize speed over texture, output over craft, visibility over depth. In those conditions, beauty gets reduced to a moodboard or a purchase, rather than something slowly made, tended, and lived with.

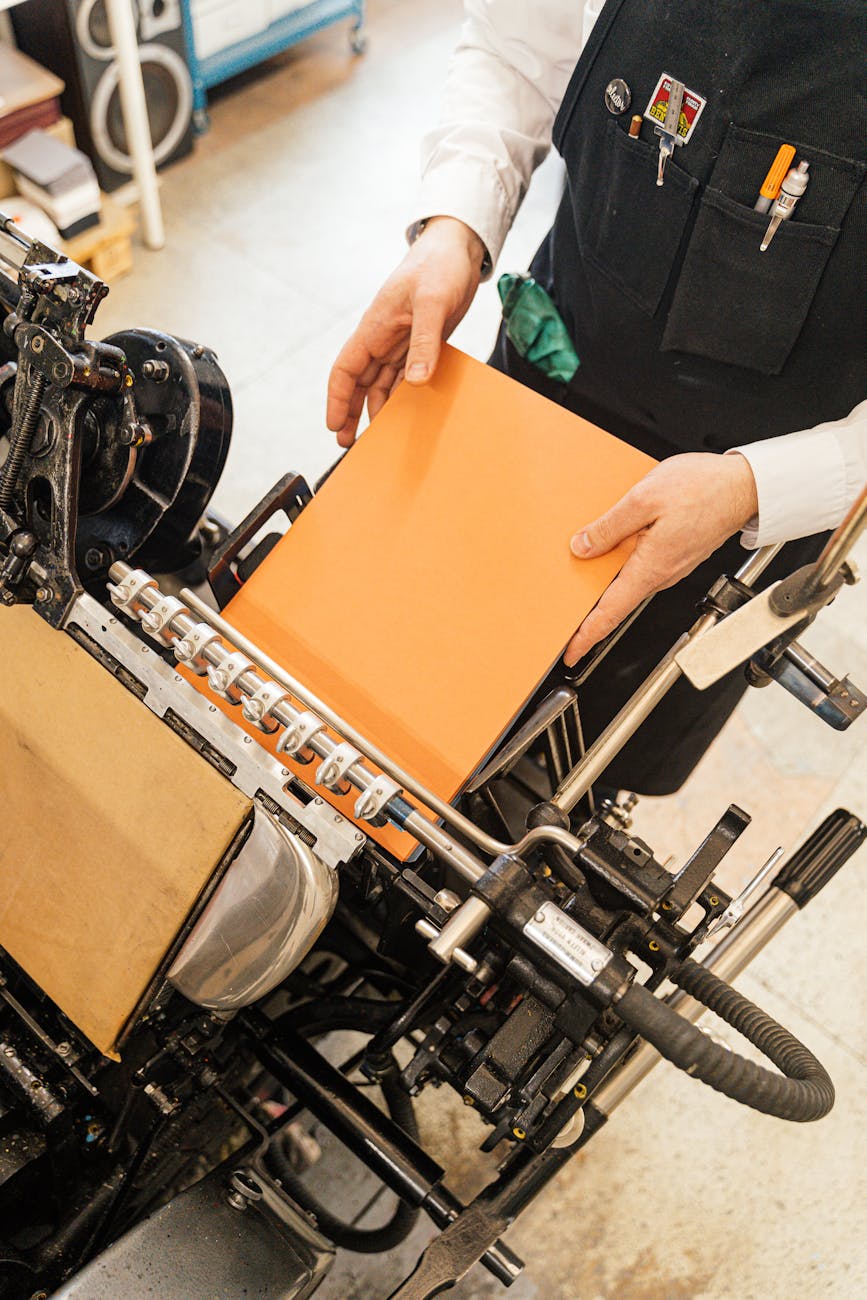

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, partly because of a bit change in my own life. For the first time ever, I now have a dedicated studio space. Writing has always been my primary genre, and I’ve long had a study for reading and writing. But this is different. The studio space (perhaps a grand phrase for a nook in my hallway) is dedicated specifically to other forms of making. There, I’ve been deepening into my bookbinding practice and working with printmaking as an adjacent art form. I recently had a first go at basketweaving, with the very practical intention of making baskets to organise my supplies. The baskets are imperfect, slightly unruly, unmistakably beginner objects. And I love them.

None of this is productive in the way productivity culture understands the term. But all of it has made my days feel more coherent, and, ultimately, more inhabitable. Beauty, here, isn’t about refinement or taste. It’s about the relationality of being in contact with materials, rhythms, and limitations that writing alone doesn’t always provide.

William Morris famously argued that we should have nothing in our homes that we do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful. That line gets quoted endlessly, often stripped of its political teeth. Morris wasn’t advocating for aesthetic minimalism; he was protesting industrial alienation. Beauty, for him, was bound up with labour, dignity, and the refusal of shoddy work—both material and spiritual.

In our own moment, the danger is not mass production alone, but abstraction. So much of our creative life now happens at one remove: ideas about ideas, plans for work, identity statements about what kind of person we are or hope to be. Beauty interrupts that abstraction. It brings us back into contact. This matters for creativity because creativity does not thrive on pressure alone. It thrives on nourishment. And nourishment is often sensory, spatial, temporal. The feel of tools. The pleasure of order that isn’t obsessive. The satisfaction of materials finding their place.

I see this again and again in my work with writers, artists, and academics. Their creative lives have been stripped of beauty in the name of seriousness. Desks become battlegrounds. Time becomes an enemy. Work becomes a referendum on self-worth.

Under those conditions, abundance sounds either naïve or manipulative—another thing to perform, another mindset to adopt correctly. But abundance, as I understand it, has very little to do with positivity or belief. It has to do with noticing what is already available and learning how to stay in relationship with it.

Beauty helps with that. Beauty slows us down just enough to notice. It widens attention without demanding that we be exceptional. It restores a sense that life—and work—can be met, rather than conquered.

This is one of the underlying currents running through my latest work, and it’s very much present in the upcoming 5 Days of Creative Abundance programme I’m hosting in March. The series isn’t about doing more or trying harder. It’s about restoring conditions in which creativity can move again—conditions that include time, permission, structure, and yes, beauty.

Across the five sessions, we’ll be exploring how creativity becomes knotted up with pressure and identity performance, and how to loosen that knot without abandoning seriousness or commitment. We’ll look at how to make time more porous, how to let work approach you rather than always forcing it, and how to keep creative energy circulating so it doesn’t feel so easily depleted. Underlying all of this is a simple proposition: creativity does better when it feels welcomed into your life, rather than squeezed into it.

When you care about how things feel, how spaces hold you, how materials respond, you are already practising a different relationship to your work. One that is less extractive. Less adversarial. More sustainable.

If that resonates, the Creative Abundance programme might be a good place to explore it further. The sessions are short, live, and recorded if you can’t make them in real time. They’re designed to meet people who are tired of hype, allergic to rigidity, and still deeply committed to their work.

Beauty won’t solve everything. But without it, we ask our creative lives to run on willpower alone. And willpower, as many of us know by now, is a brittle fuel.

Sometimes what we need is not a new strategy, but a more liveable ecology. A desk that invites us back. A practice that feels companionable. A sense that what we are doing belongs to a life, not just a ledger of outputs.

Beauty helps us remember that. And remembering, in this case, is not nostalgic. It’s practical.

If you’d like to spend a week exploring what abundance might look like when it’s grounded in attention, care, and lived experience, I’d love to have you join us in March.

Upcoming Events

Creative Flow Co-Working Session: Deepening Your Craft

16 February | 10 AM-12 PM GMT | FREE

Register here: https://www.meetup.com/the-art-of-creative-practice/events/312151262/

Beyond Time Management: A More Natural Way to Organise Creative Work

24 February | 7.30-9.00 PM GMT | £12

Register here: https://www.meetup.com/the-art-of-creative-practice/events/313062163/

5 Days of Creative Abundance

9-13 March | 7.30-8.00 PM GMT | £29

Register here: https://www.meetup.com/the-art-of-creative-practice/events/313206797/

The Writer’s Flow Circle: A 12-Week Group Coaching Circle

Beginning Monday 23 March | 7.30-9.00 PM UK time | £180

Register here: https://www.meetup.com/the-art-of-creative-practice/events/313207235/