As I prepare for some very exciting spring workshops and begin working with a new cohort of 1–1 clients, I find myself returning again and again to the question: what kind of attention are we cultivating? And to what ends?

At the same time, I am collaborating with colleagues at the University of Surrey on a research study exploring the relationship between mindfulness and originality. I have designed an 8-week Mindfulness for Originality programme that we are currently trialing, and we will be studying its outcomes over the coming months. The premise is simple but, I think, quietly radical: that sustained, non-reactive attention is not the enemy of creativity but its precondition.

This runs counter to a certain romantic myth of originality as frenzy. But when we examine the intellectual lives of figures like Hannah Arendt, James Baldwin, or Virginia Woolf, what we find is not scattered brilliance but disciplined depth. Woolf’s diaries are full of labour—patient, iterative, attentive labour. Originality emerges not from distraction but from fidelity.

The philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that we have moved from a disciplinary society to an achievement society, in which the violence is internalised. We exhaust ourselves trying to be endlessly responsive. The result is not freedom but fragmentation. In Stolen Focus, Johann Hari traces how economic and technological systems have steadily eroded our capacity for sustained attention, not as an accident but as a business model.

The ethics of attention, then, must reckon with power.

Who profits when we are distracted? Who benefits when we can’t read a long book, hold a complex argument, or sit with a difficult feeling?

Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows made this argument over a decade ago, but the evidence has only intensified. We are training our brains toward interruption. And yet, paradoxically, we long for immersion.

I see this longing in my coaching practice. People do not come to me because they lack ideas. They come because they cannot hold their ideas long enough to deepen them. They skim their own lives.

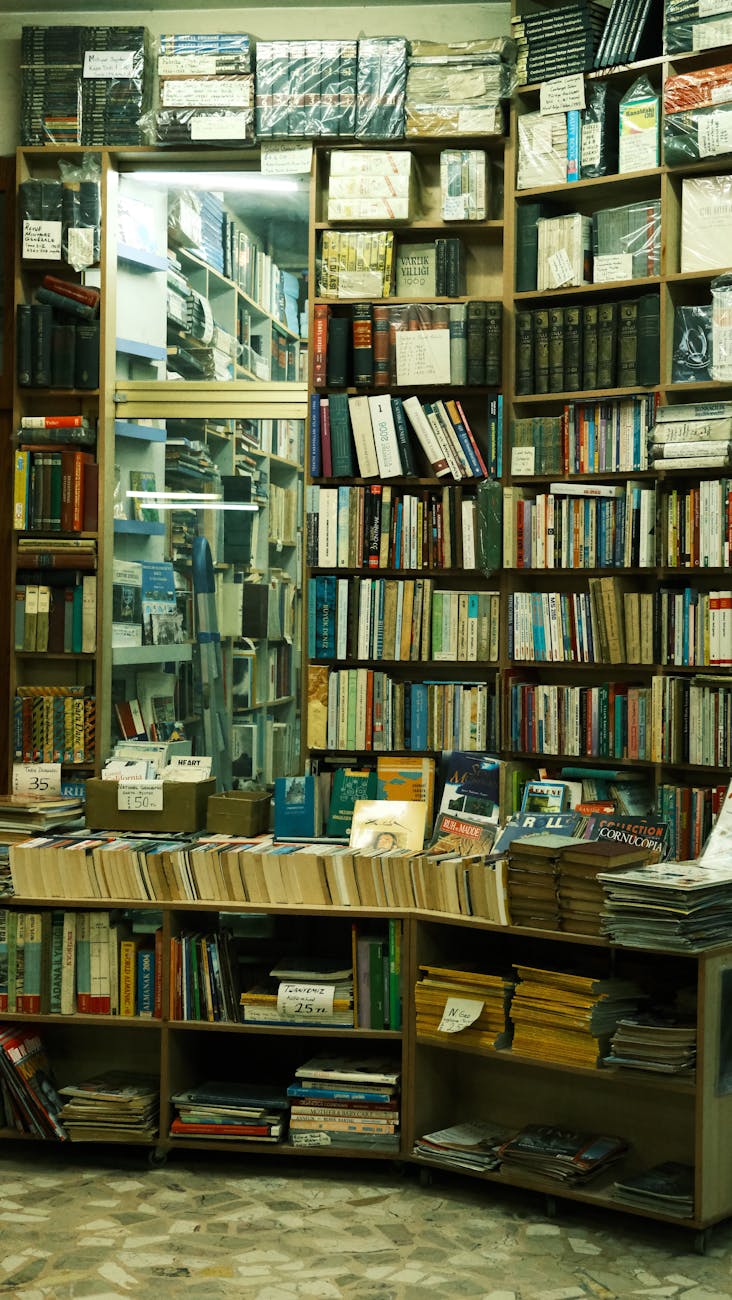

Reading, in this context, becomes a form of resistance.

To read a demanding text—say, a passage from To the Lighthouse or a dense philosophical argument—is to enact a countercultural choice. It says: I will not be hurried. I will not reduce this to a headline. I will allow complexity to exceed me.

But attention is not only about texts. It is about how we inhabit our own projects.

In the 8-week programme we are trialling at Surrey, one of the early exercises invites participants to notice the precise moment at which they reach for distraction during creative work. Not to judge it. Not to suppress it. Simply to witness it. The findings, even anecdotally, are striking. Original insights tend to arise not in the first burst of enthusiasm but in the stretch just beyond discomfort—when one stays.

There is an ethics here, too. To stay with one’s work is to honour it. To stay with another person is to dignify them. To stay with oneself—especially in the face of uncertainty—is to cultivate integrity.

This is why I am so passionate about the upcoming 5 Days of Creative Abundance workshop (9–13 March, 7.30–8.00 PM GMT, £29).

Yes, it is a practical, energising, five-day immersion into creative flow. Yes, it will give you tools, structure, and momentum. But underneath that, it is an experiment in attention.

For five evenings, we gather. We turn toward what matters. We practise not skimming our own creative impulse.

Abundance, as I understand it, is not accumulation. It is depth. It is the experience of discovering that when you attend properly to one idea, it unfolds. When you give something your full presence, it yields more than you expected.

There is a quiet confidence that arises from this. Not the performative confidence of broadcasting productivity, but the grounded confidence of knowing you can enter and remain in meaningful work.

If you have been feeling scattered, thinly stretched across platforms and obligations, this workshop is designed for you. If you sense that there is more in you—but you can’t quite access it amid the noise—this is for you.

I am intentionally keeping the price accessible (£29) because I want the barrier to entry to be low. But do not mistake accessibility for superficiality. The container will be strong. The invitation will be serious.

You can register here:

https://www.meetup.com/the-art-of-creative-practice/events/313206797/

And if you are ready for more sustained support, my 1–1 coaching work continues alongside these group offerings. In those spaces, we go deeper. We examine not only habits of attention but the attachment patterns and identity narratives that sustain them. We design structures that protect what is most alive in you. It is precise, relational, and tailored.

Attention, I am increasingly convinced, is a form of stewardship.

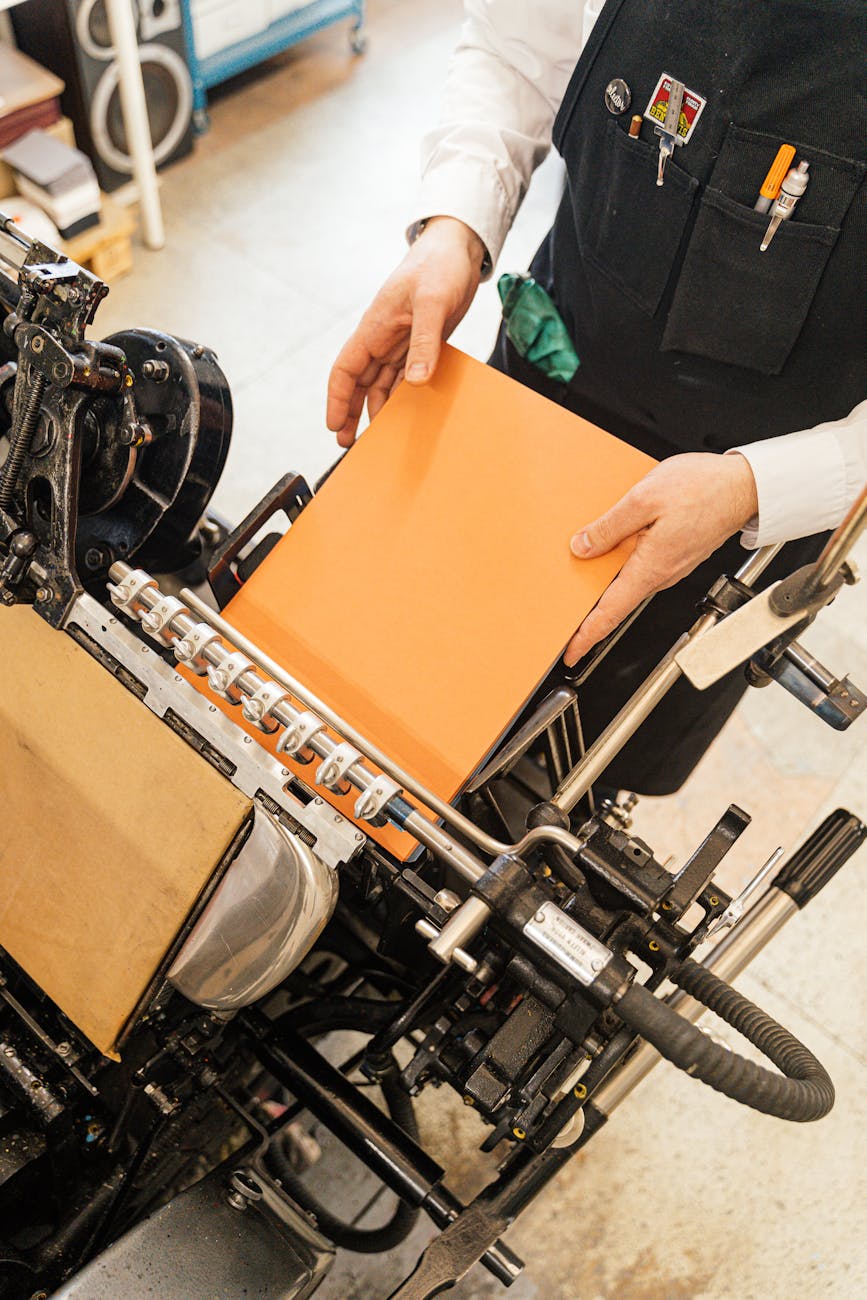

In an earlier book project, I explored the ethics of mediation in mail-order occultism—how printed texts promised transformation across distance. I am struck now by how similar the stakes feel. Every medium shapes consciousness. The question is whether we use the medium deliberately or allow it to use us.

Marshall McLuhan’s famous dictum that “the medium is the message” was not a celebration; it was a warning. If our dominant medium fragments attention, then our inner lives will fragment accordingly—unless we intervene.

This intervention need not be dramatic. It begins with small, repeatable acts. Reading ten pages with full presence. Writing one paragraph without checking a phone. Listening to a friend without composing a response.

It also requires community.

One of the reasons I continue to run workshops—even as I refine my focus and prepare for new directions—is that collective attention is amplifying. When we gather around a shared intention, distraction loses some of its grip.

There is something profoundly moving about watching a group of people choose depth together.

In my own life, this season feels like a threshold. New 1–1 clients. Spring workshops taking shape. Research that, I hope, will contribute something meaningful to the conversation about mindfulness and creativity. It is not frenetic expansion. It is intentional cultivation.

And so I return to the ethical question.

What deserves your attention?

Not what clamours for it. Not what monetises it. What deserves it?

Your most original ideas do not shout. They wait. They require a certain stillness before they reveal themselves.

If you would like to practise that stillness—and discover what abundance might mean in your creative life—I would love for you to join me for the 5 Days of Creative Abundance.

Register here:

https://www.meetup.com/the-art-of-creative-practice/events/313206797/

Attention is not merely a mental resource. It is the substance of a life.

And how we give it—what we allow it to shape—may be one of the most consequential ethical decisions we make.