In 2026, I’ll be undertaking a deliberately anachronistic experiment.

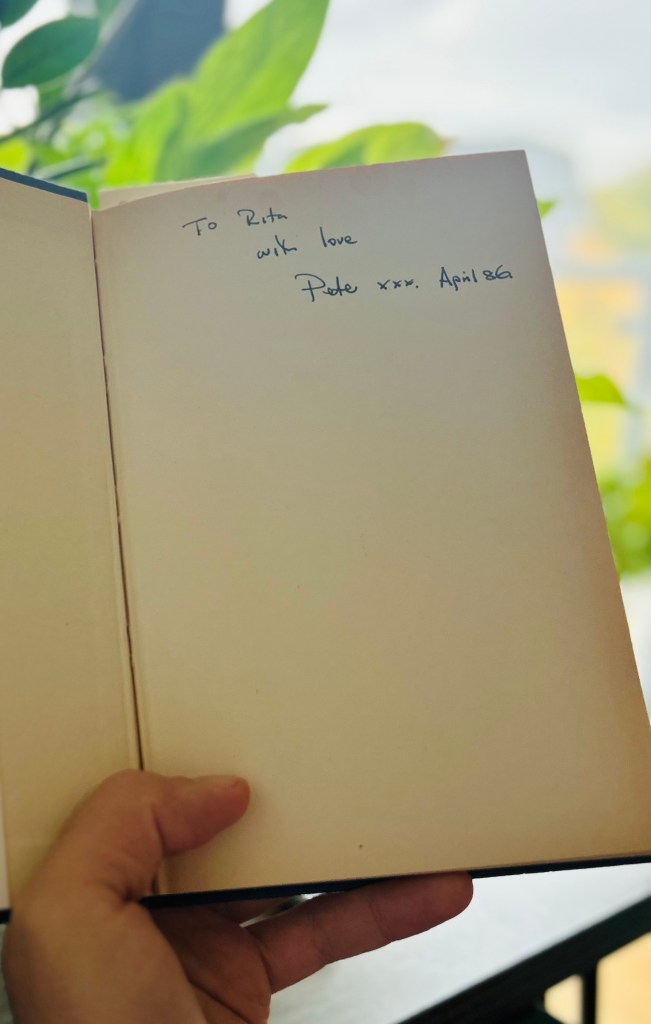

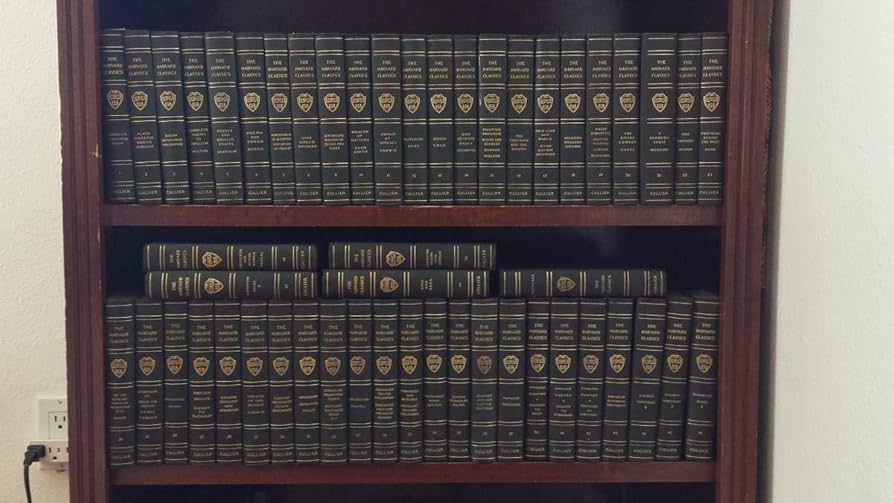

Each day for the coming year, I’ll be reading for around fifteen minutes from the so-called ‘Five-Foot Shelf’, the early twentieth-century Harvard Classics series assembled by Charles W. Eliot and promoted as a complete liberal education for the working adult. I’ll be following Eliot’s original prescription closely: not bingeing, not accelerating, not ‘optimising’, but reading at the pace he proposed, in the order he set out, according to the widely circulated ‘fifteen minutes a day’ schedule that accompanied the series.

What interests me is not whether Eliot’s claim still holds in any literal sense, but what happens when such a rhythm is taken seriously now, by someone already saturated in reading, already professionally formed, and already deeply aware of the limits of any canon.

Because I read constantly for my day job.

As an English literature professor, reading in depth is not optional; it is the ground of the work. I read intensively, repeatedly, and often narrowly. I return to the same texts across years and decades. I read them historically, theoretically, critically. I annotate, teach, publish, and argue with them. Some of the works on the Five-Foot Shelf fall squarely into this category: texts I’ve read many times, taught in multiple contexts, or written about in peer-reviewed research.

Others, however, are unfamiliar, sometimes embarrassingly so. Texts I’ve skimmed but never lived with, heard cited but never read end-to-end, or vaguely assumed I would ‘get to’ one day. Encountering these side by side, under the same modest daily constraint, is part of the experiment.

It’s probably worth saying, explicitly, that this project is not an attempt to resurrect a Great Books curriculum or to smuggle the ‘canon’ back in through the side door. I am well aware of the canon wars, and sympathetic to many of the critiques: the exclusions they exposed were real, consequential, and long overdue. The idea that a single, authoritative list of texts could stand in for ‘universal’ culture is no longer tenable, and nor should it be.

What interests me, then, is not the Five-Foot Shelf as a claim to authority, but as a historical artefact and a formative device. It is a record of how liberal education was once imagined, packaged, and sold to hard-working, well-meaning people for whom formal education was not a practical reality. Reading it now allows us to ask not ‘Is this the canon and is it good or right?’ but ‘What did this structure think reading was for?’ What habits of mind did it privilege? What kinds of judgment did it aim to produce?

There is also value—both intellectual and ethical—in encountering texts that do not immediately affirm our assumptions or reflect our intellectual formation. Not because they are beyond critique, but because critique itself is deepened by sustained engagement rather than dismissal at first contact. The fifteen-minutes-a-day format matters here. It resists both reverence and rejection, asking instead for patience, repetition, and the willingness to let one’s responses evolve over time.

In that sense, the project is as much about format as it is about content. A fixed sequence, a modest daily commitment, and a year-long horizon create conditions that are increasingly rare in contemporary reading life. What emerges under those conditions—agreement, resistance, boredom, insight, irritation—tells us something not only about the texts, but about ourselves as adult readers navigating a fractured, accelerated intellectual landscape.

This project is about breadth, deliberately undertaken alongside a professional life structured around depth.

In contemporary intellectual culture, depth is rightly prized. It is associated with rigour, expertise, and responsibility. Breadth, by contrast, is often treated with suspicion: dilettantism, surface knowledge, or the scattered attention of the generalist.

Liberal education, as it was originally imagined, did not ask readers to choose between breadth and depth. It assumed that serious engagement required both: immersion in particular problems and exposure to forms of thought beyond one’s immediate specialism. Breadth was not a substitute for depth; it was a condition for judgment.

The Five-Foot Shelf was an attempt—flawed, exclusionary, ambitious, and yet sincere—to provide such breadth to adults who were already working, already formed, already busy. Its claim was not that fifteen minutes a day would make one an expert, but that it could sustain a relationship with the wider inheritance of thought, language, and ethical imagination.

Depth sharpens tools. Breadth calibrates them.

Depth teaches us how to see clearly within a frame. Breadth reminds us that frames exist.

As someone whose professional life is structured around long reading days, sustained writing periods, and deep immersion, this constraint feels oddly corrective. It returns reading to a scale that is neither performative nor instrumental.

What matters is not how much ground is covered, but the continuity of attention. This is one of the lessons adulthood keeps teaching us: formation happens not through intensity alone, but through return.

One of the persistent myths of academic life is that learning culminates in mastery. That once one has specialised, published, and secured a position, one’s relationship to knowledge stabilises.

In practice, the opposite is often true. Expertise narrows responsibility. It brings obligations: to texts, methods, and debates that demand constant upkeep. Over time, this can subtly crowd out curiosity—the kind not immediately justified by relevance or outcome.

Some of the most important intellectual experiences of adulthood occur not when we deepen what we already know, but when we allow ourselves to become beginners again, within a structure that does not require us to justify that choice.

This is lifelong learning in its older, less marketable sense: not continuous upskilling, but sustained openness. I am an academic, and I will always read for work. But I also read for pleasure, understanding, and character development. The distinction matters.

One of the things institutions once did—however imperfectly—was structure intellectual aspiration. They told us what counted, what came next, and what completion looked like. As those structures loosen or disappear, the burden of decision shifts inward.

What do I want to know?

What deserves my attention now?

What kind of reader—and thinker—am I still becoming?

The Five-Foot Shelf functions here not as an authority, but as a scaffold. It provides a sequence that frees me from constant choice, while still leaving me responsible for the meaning I make of it.

This is why setting personal educational goals matters so much in adulthood. Without them, learning becomes reactive, fragmented, or indefinitely deferred. With them, even modest commitments—like fifteen minutes a day—can accumulate surprising force.

An Invitation

If this project speaks to you, it’s likely because you’re someone who thinks carefully about how ideas, attention, and intention interact. You may have more ideas than hours, more commitments than containers, and a sense that what’s missing is not motivation but shape.

That is exactly what Reflect & Reset: Quarterly Planning Workshop (R&R Q1) is designed to provide.

This 90-minute online workshop, taking place on Monday 5 January 2026 (7:30–9:00pm GMT), offers a structured, spacious way to step back from the rush of the new year and decide—deliberately—what the next three months are for. It’s for creatives, thinkers, and reflective practitioners who value depth, but know that depth needs rhythm if it’s going to survive contact with real life.

During the session, I’ll guide you through my Reflect & Reset Map system: an evidence-based framework that combines reflection, prioritisation, and light structure. Together, we’ll clarify what genuinely matters to you in January, February, and March, translate that into a small number of meaningful commitments, and shape a plan that respects both your inner life and your outer responsibilities.

If you’re starting 2026 with questions about focus, learning, creative work, or how to hold serious intentions without burning out, this workshop is an ideal place to begin. Bring your journal and your favourite hot drink. I look forward to seeing you there!